Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away is a film that lives in the heart of modern cinema, a timeless fable of courage and identity. For decades, audiences and critics alike have praised its whimsical characters and profound allegorical story. Yet, to focus only on the narrative is to miss the quiet, foundational magic that holds the entire masterpiece together: its world.

This is not an analysis of what the story means, but of where it happens. We will journey with Chihiro, not through her character arc, but through the physical spaces she inhabits, deconstructing how Miyazaki’s direction and the breathtaking background art create an architectural marvel that remains unparalleled in animation.

Crossing the Threshold: From the Mundane to the Magical

Every great journey begins with a single step across a boundary, and Miyazaki uses the environment itself to establish these critical transitions. The film’s opening is a masterclass in building atmosphere through location. The abandoned theme park Chihiro and her parents discover is not just a generic “spooky” place; its architecture is a deliberate and unsettling fusion of traditional Japanese and fading Western styles. This visual dissonance, combined with the overgrown landscape and the ever-present sound of the wind, creates the powerful sense of a place with a forgotten, unnatural history.

The true boundary is the wide, dry riverbed. In mythology, crossing a river is the archetypal point of no return. Miyazaki visualizes this by making the world on the other side operate under fundamentally different rules. As the sun sets, the serene, empty town transforms. Lanterns flicker to life, and the translucent bodies of spirits begin to coalesce. The environment itself enforces the laws of this new reality.

A Vertical Society: The Living Architecture of the Aburaya

Once across the bridge, the bathhouse ceases to be a destination and becomes the entire world. Miyazaki brilliantly establishes its geography and social structure through a dizzying, yet perfectly logical, vertical journey.

The Boiler Room: The Industrial Heartbeat

Chihiro’s perilous descent down a decaying outer staircase is not just a visual thrill; it is the physical manifestation of the crisis that, in Miyazaki’s words, forces her “‘strength of adaptation and her perseverance’ to rebound.” She enters the bathhouse’s living engine room: Kamaji’s boiler room. The spatial continuity is flawless. The art direction is a symphony of organized chaos, dominated by hundreds of dark, wooden drawers meticulously labeled with Kanji for herbal remedies—薬 (kusuri). This tells us the bathhouse’s magic is rooted in traditional pharmacology. The space is dark and grimy, the industrial underbelly where the magical and the mundane intersect to power the luxury above.

The Grand Hall: A Symphony of Traditional Artistry

Ascending into the main bath floors, the screen explodes with detail. The entire hall is constructed from a deep, dark, polished wood, evoking the sacred feel of a historic temple. The walls are a maze of delicate shoji screens and magnificent fusuma panels adorned with exquisite, hand-painted murals of cranes and cherry blossoms. This grounds the spirit world in a deep reverence for nature. Even the tools are intricate: the faucets are carved wooden dragon heads, and the bath tokens are exchanged for herbal infusions drawn from massive, labeled cabinets. It is a space that is simultaneously a sacred place of purification and a bustling, functional business.

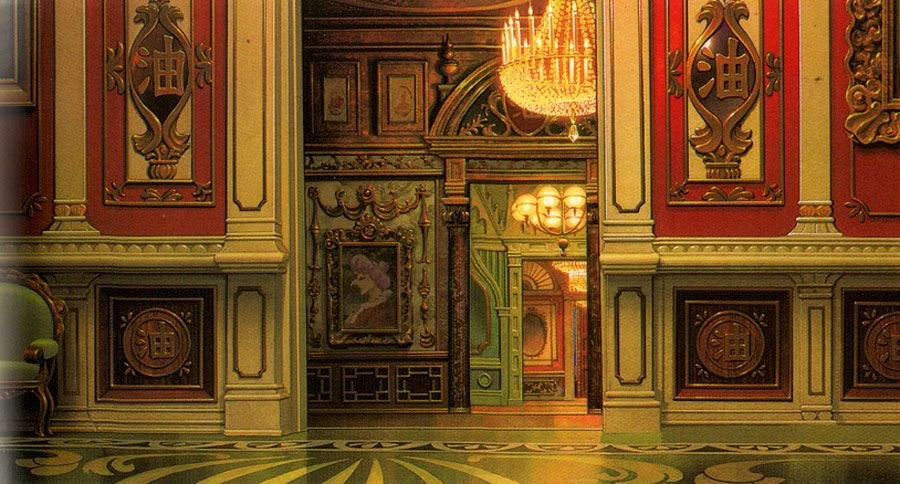

Yubaba’s Penthouse: A Prison of Greed and Cultural Clash

The final ascent of the Aburaya takes Chihiro to Yubaba’s office, and the visual shift is immediate and jarring. The traditional Japanese aesthetic vanishes, replaced by an overwhelming, cluttered, and distinctly Western opulence. The floor is not warm wood but thick, gaudy, European-style floral carpets. Yubaba’s massive, Rococo-style desk functions as a throne of commerce, while the room is filled with heavy, cushioned armchairs—furniture of individual status, not communal living. This jarring cultural clash is an intentional choice. As Miyazaki himself stated, “The fact of giving the world where Yubâba lives a Western side suggests something that we have already seen somewhere without being able to distinguish between the dream and the real… it is a melting pot.”

This “melting pot” is a chaotic museum of acquired “treasures”: blue-and-white porcelain vases and stuffed animal heads on the walls, a symbol of conquest completely alien to the harmony with nature seen below. Her greed is so all-consuming that it even smothers her own child, whose nursery is a suffocating prison of silk cushions and imported toys.

The Horizontal Journey: Escaping the Aburaya’s Walls

After meticulously establishing the bathhouse as a self-contained, vertical world, Miyazaki masterfully expands his canvas with the hauntingly beautiful train sequence. The continuity is again impeccable: Chihiro exits through a hidden side door in Kamaji’s boiler room, opening directly onto the flooded plains. This architectural detail reinforces the boiler room’s role as a functional hub connected to the outside world, separate from the grand entrance for guests.

The journey itself is a masterpiece of atmospheric background art. The world outside is a quiet, melancholic landscape of endless, shallow water under a perpetual twilight sky. The genius is in the tangible details: the train tracks are visibly submerged; its interior, with velvet seats and warm incandescent lights, feels real and nostalgic. The train stops at solitary, unnamed island stations where shadowy, featureless spirits silently embark and disembark. In the far background, the silhouettes of telephone poles and distant houses with their lights on suggest a civilization that is both near and impossibly far away. This horizontal journey is the thematic and architectural opposite of Chihiro’s frantic, vertical climb. The bathhouse was a world of noise and labor; the train ride is a moment of profound, introspective silence.

A Tale of Two Worlds: The Penthouse vs. The Cottage

The train’s destination, Zeniba’s cottage at Swamp Bottom, provides the film’s most profound architectural contrast, crystallizing the film’s core theme. Where Yubaba’s home is a monument to greed, Zeniba’s is a celebration of self-sufficiency and warmth.

The cottage is small, rustic, and built from natural materials. Its centerpiece is not a desk, but a warm, crackling fireplace—a symbol of nourishment. Every object has purpose and a sense of personal touch: a spinning wheel, simple wooden furniture, and hand-knit goods. Zeniba’s world is one of creation, where value comes from what one can make; Yubaba’s is one of endless acquisition. Zeniba’s home is a place of welcome, where equals sit together at her table, a stark difference to the intimidating hierarchy of Yubaba’s office. Miyazaki uses these two spaces to argue that a simple life of meaningful work and community is spiritually richer than one of isolated, materialistic greed.

More Than a Drawing: The Enduring Power of a Believable Place

What makes Spirited Away endure is the unshakable feeling that the world Chihiro visits could actually exist. This is Hayao Miyazaki’s ultimate magic trick, performed not with spells, but with masterful direction and painstaking artistry. He did not create disconnected, beautiful paintings; he built a coherent architectural space, a world with geography, plumbing, and a soul.

This is a direct answer to Miyazaki’s own concern that “men who have no history and the people who have forgotten their past will disappear.” He did not just create a fantasy; he intentionally built a “place with a past, a story” to give his cinematic world a “new persuasive force.” The journey from the bridge to the boiler room, the transition from the vertical bathhouse to the horizontal sea, and the final contrast between the twin sisters’ homes are not just plot points; they are lessons in spatial awareness that ground the film’s most fantastical elements in a tangible reality.

In an age of digital shortcuts, the handcrafted continuity of Spirited Away stands as a testament to a more deliberate kind of world-building. It reminds us that to truly transport an audience, you must not only show them a magical world but also give them a map to believe in it. And for over two decades, the world has believed.

This level of thematic depth is what defines a masterpiece, separating it from stories that rely on spectacle over substance.

All images are screenshots from their respective anime series or are in the public domain, and are used under Fair Use for the purpose of criticism and commentary. Sensei Square is an unofficial fan work and is not affiliated with the original copyright holders. © All rights reserved to their respective owners.